During the time I lived in China, the country changed so much.

I wondered how our own perspectives influence the way we perceive that change, and who gets to tell the stories.

What is the difference between an insider’s perspective, and an outsider’s? What happens when you straddle both, when you have two homelands? How does your perspective change?

I invited a few Substackers to riff on this concept of change, in China.The contributors are

, and .The following is a collage of perspectives.

Can you get jet lagged from how time flies?

It seems in the 70 years of my parents’ life, they’ve lived through 200 years worth of history. From farmlands to cities and oil lamps to AI-powered everything.

In Chinese mythology, the time difference between the heavenly realm of immortals and the realm of humans on earth is vast. A day in heaven usually counts for one, or several years on earth in different stories.

To imagine time expanding and shrinking, like lungs, makes me ponder on the tenacity of the cosmos.

“Change” has become China’s defining term.

It permeates every domain, every facet of life. The efficiency of transformation is impressive, yet confusing. Is this still the hometown I knew? Standing at a crossroads, I watch the flow of pedestrians: no more nodding greetings. Every passerby hunches at a 90-degree angle, necks craned, thumbs scrolling across glowing brick. Perhaps becoming “smartphone zombies” offers introverts shelter from social demands. Or maybe the screens themselves create new generations of the socially avoidant.

When we talk about change in China, the headlines usually point to skyscrapers, GDP, or bullet trains. Less attention is paid to a subtler transformation: China’s rise as a cultural power. When I lived there in the mid-2000s, the gravitational pull came from elsewhere. The United States mainly, with Japan as the cooler cousin. Chinese teenagers idolised NBA stars, traded pirated Hollywood DVDs, and copied the looks of J-pop idols. Local brands, local stars, local anything: none of it seemed to carry the same weight. China seemed to know what it lacked. Those years felt like a time of absorption rather than projection. You could sense the hunger to consume, to imitate, to catch up. Culture, like technology, was still imported.

How does it feel to grow up sleeping on a turf platform furthest from the oven to sleeping in a perfectly temperatured room? From boarding your first plane in your 30s to having to flee the capital in a private hire in order to escape the ravaging policies of a pandemic?

History is a long game.

In less than a generation, the cultural current has shifted. Today, Chinese cinema regularly dominates its own box office. Homegrown pop stars headline stadium tours. Domestic brands, from fashion to tech, shape regional tastes. Where once K-dramas and American sitcoms set the tone, now it’s Chinese fantasy epics and viral social media platforms that ripple outward. This change is not uniform, nor without resistance. Western influences are still there, still powerful. Yet the balance has tipped. What once seemed peripheral is now central, and the confidence of that change is palpable.

Living abroad as a traveler, outsider, and expat, each return to China offers fresh and intriguing perspectives. Every year, new skyscrapers rise from the ground, roads are redesigned, and cityscapes transform. Downtown skylines expand dramatically, streetlights glow like artificial suns, and even smaller cities now pulse with a tech-vibrant energy. In contrast, the US is in a different world. In cities like New York or San Francisco, annual change is barely perceptible. Some streets and buildings stand unaltered for two centuries.

When I lived in Suzhou, there was a rumour a new building appeared in Shanghai everyday. I’m sure it was true. It was if they just shot up, as if scaffolding was fed with magic beans and they sprouted, just like Jack’s beanstalks.

The overnight train rides to Northeast. How the wagons rocked my whole family to sleep, or triggered a conversation with strangers. When we travelled in compartments with six beds, we’d befriend others going North, and share peaches, sunflower seeds, stories.

The same distance takes no more than 5 or 6 hours now. The high speed trains are impressive, efficient, quiet. When you want to eat, your order via your phone, and the food gets delivered directly to your seat. When you look out the window, every inch of land is cultivated.

The conversations I now have are different. In quiet voices, my dad and I speak of the past and vanishing medicinal plants. There’s stagnation in the North; abandoned buildings that stand like mountains in the land. Between Beijing and Tianjin, the mountain rocks look strange. Little by little, they have been shaved to distorted sculptures, their material serving to build more apartment blocks. Down in the cities, the stagnation reflects in people as well, as heat pathogens attack the heart, lung, and skin.

From the shrill sound of steam released from the boiler room in a town that that had no need for boom-gates; everybody knew to stop for incoming trains

to wide, huge, chairs placed carefully far away from bothersome neighbours, positioned so each seat hosted a view out of the wide, glassed, front windows,

I watched the transformation of China, one railway seat at a time.

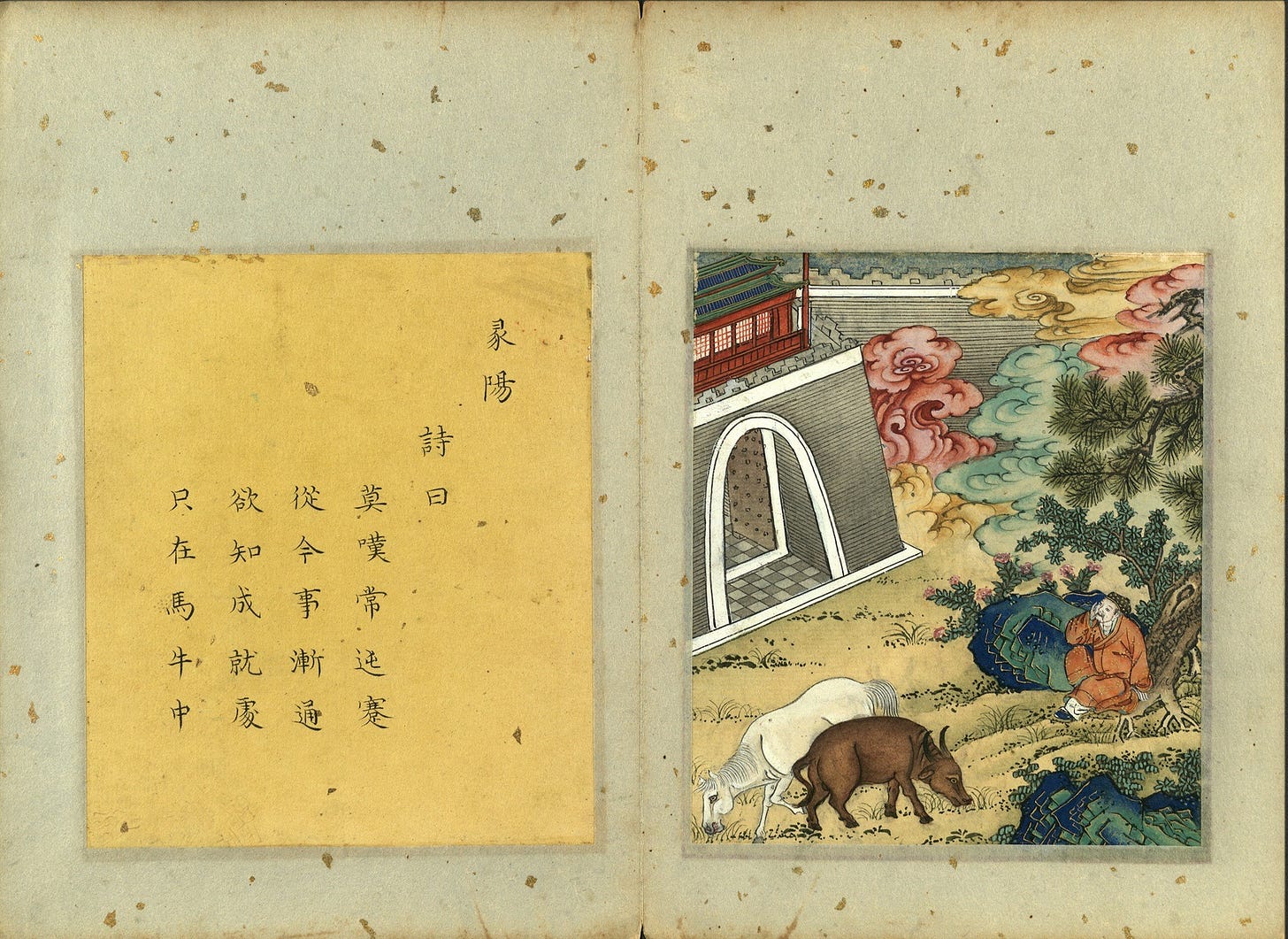

I had known Moon Hill only in pictures - its great limestone arch gracing postcards along West Street, improbably perfect, like some celestial aperture punched into the sky. Yueliang Shan, the locals called it. Legends clung to it like cobwebs. Some whispered the moon had once come to rest there, stooping low to kiss the earth before lifting away again. Others said it was the bridge of an immortal, abandoned when heaven and earth grew too far apart. I had little faith in such stories, but they drew me nonetheless - as if the hill itself had been calling my name, waiting for a stranger to answer.

I stayed on. Some places demand silence, not speech. I thought of the poets who might have stood here centuries ago, touching the rock as I did now, their words dissolving into time. Perhaps they, too, had climbed alone, watching mist curl between the peaks. Perhaps they, too, had felt - as I felt now - that the world below could wait.

When at last I descended, I glanced back once at the arch - a solitary ring of stone against the sky - and felt as if I were leaving not just a place but a moment outside of time.

In the early 2000s, it seemed like everything could go well for a while. My childhood summers in China are full of a kind of sensuality that holds a forgotten world deep in the tissues of my body. Dust curtains in the streets, shouting vendors, Mao’s face on red bills, folded into half and stuffed into my pocket by grandmother’s wrinkled hands. I remember tanned and toothless faces, aunts and uncles selling me sugar cane off donkey-pulled carts, the way the juice made my fingers stick.

Hot nights in Tianjin before my grandparents got an AC, the feeling of skin against a mahjong bamboo mat - a queensize topper made from bamboo shaped into tiny mahjong-style tiles.

The rhythm of grandmother’s fan as mother’s wrist moved up and down, the subtle creaking of wood and paper, and the breeze that felt like summer by the sea.

It might be true that becoming a “smartphone zombie” isn’t entirely by choice: our devices have become an indispensable tool in modern life. Every essential function now flows through smartphones: paying utility bills, booking medical appointments, purchasing travel tickets, requesting repair and maintenance services, grocery shopping, public transportation, entertainment, and even work communications with colleagues and clients.

Beyond the proliferation of apps, WeChat reigns supreme in daily life. Its mini-programs seamlessly integrate countless services, while the platform itself merges messaging (text/voice/video), social networking, and payment systems.

Cash has become nearly obsolete; from department stores to farmers’ markets, even street vendors display QR codes for WeChat Pay. The app has so thoroughly saturated Chinese society that living without it makes you a social weirdo—you’d be viewed as some digital-age outcast. We’ve willingly (or unwillingly) surrendered to this ecosystem. The convenience is undeniable, but at what cost? Our autonomy dissolves with every “ding” of a notification, every reflexive reach for the glowing brick. The very tools meant to connect us now mediate, and often replace, genuine human interaction.

I remember a pair of shower slippers that my grandfather wore in 2005. It had the 2008 Olympics logo on it, the first product echoing from a future that would bemuch, much changed. The next time I visited, grandpa was gone, and the capital suddenly had several subway lines, running per routine like it had never been any different. Another time, I looked out the window from our flat in Beijing, and noticed a whole mall complex that had showed up in the year that I had been gone. I ran to my parents to tell them about it, but it wasn’t news to them. Change isn’t always acknowledged. Especially when you’ve lived a life where changes have chased you plenty, dressed in green uniforms carrying red books...

A new mall appearing in the neighbourhood was a small, irrelevant change on their map. A drop of water in a sea of ghosts.

Last month, when I returned to China and waited at Beijing Capital International Airport, I decided to grab a coffee. As I entered the café, I saw a white family of four, parents and two children, standing in line at the counter. I joined the queue behind them. The barista patiently explained the menu to them in English, and after what felt like an eternity, they finally completed their order. The father paid in cash. Just as I thought it was finally my turn, a barista behind the massive espresso machine suddenly yelled to me: —“Go scan the QR code over there! Don’t queue here!” I was stunned, unsure why he shouted to me. Still, I stepped forward to explain to the cashier that I couldn’t use mobile payment, only for the same barista to snap again: —“Don’t you hear me? Scan the QR code!” At that point, politeness went out the window. I raised my voice too: —“I don’t have WeChat Pay! Can I pay in cash?” The barista stared at me, wide-eyed, as if I were some alien. Even the customers behind me shot me strange looks. Only then did the cashier reluctantly ask for my order. As I waited for my coffee, I reflected on this “interesting encounter:” How deeply ingrained mobile payment has become, how people assume everyone has WeChat, uses WeChat, and cannot function without it. Any deviation from this norm brands you as an outlier.

Last year in Nanjing, I was denied entry to the subway because I didn’t have WeChat Pay. Stranded, I had to wait 20 minutes on the roadside before finally hailing a cab.

Living in China back then, it was hard to imagine this turn. The country I saw felt restless, looking outward. The China of today projects a cultural gravity of its own - one that others now orbit.

It’s difficult to talk about change in China without mentioning the 易经 Yi Jing, (previously phoneticised as I Ching) the Book of Changes. When I lived in Qingdao, I spent an inordinate amount of time looking for the house where the first translator of the Yi into a European language, Richard Wilhelm, lived.

The idea of house, of family, is pictured as a dynamic in the 37th hexagram of theI Ching - Jia Ren (家人) Smoke curls up from the fireplace in the house and draws people together.

Mother is mother, father is father - and so the siblings, too, are younger or older,and truly in their place. It is not about a fixed model of roles, it is about an energetic distribution that holds balance, like our sun system is balanced by individual orbits revolving around the sun.

The 37th hexagram is the force that gives permission to be the youngest childwhen you are the youngest child, and access to the strength and authority of“mother” to all mothers.

When things are gathered in order, change feels different. Time by the fire goes by different, too — it can actually do as time does, and pass. Not rush. Not fly. Not push, not lost between the realms.

Balance comes through rivers and lakes — and lakes on top of mountains.

Thank you Jade, Nico, and Lucia for your riveting work!

Jade will be posting more of her thoughts about change on her blog very soon. Watch out for it!

Lucia is travelling for a bit, and her most recent post is about Tolkien’s drawings and the I Ching, part of an upcoming new series.

Nico has just returned from an adventure, trying to find Bruce Chatwin’s gravesite, and will be continuing his tales of grandeur very soon. Stay tuned!

Reader, please click on the links and read more of these wonderful writers and thinkers!

That was outstanding, thank you to all of you, and especially Debbie for the concept! 👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Wonderful to get all these different perspectives -- a bit scary that you can't ride a train without WePay! The pace of change must be dizzying.